Phyllis Wheatley as Katie Geneva Cannon's Sacred Text

--by Matty Marrow

The passage below details a monumental moment in not just Black American history, but the history of Black American women. It can be found repeatedly, almost word for word, in the works of Katie Geneva Cannon. Rev. Dr. Cannon uses this story of Phyllis (also spelled Phillis) Wheatley’s oral examination to demonstrate several of her key womanist ethics:

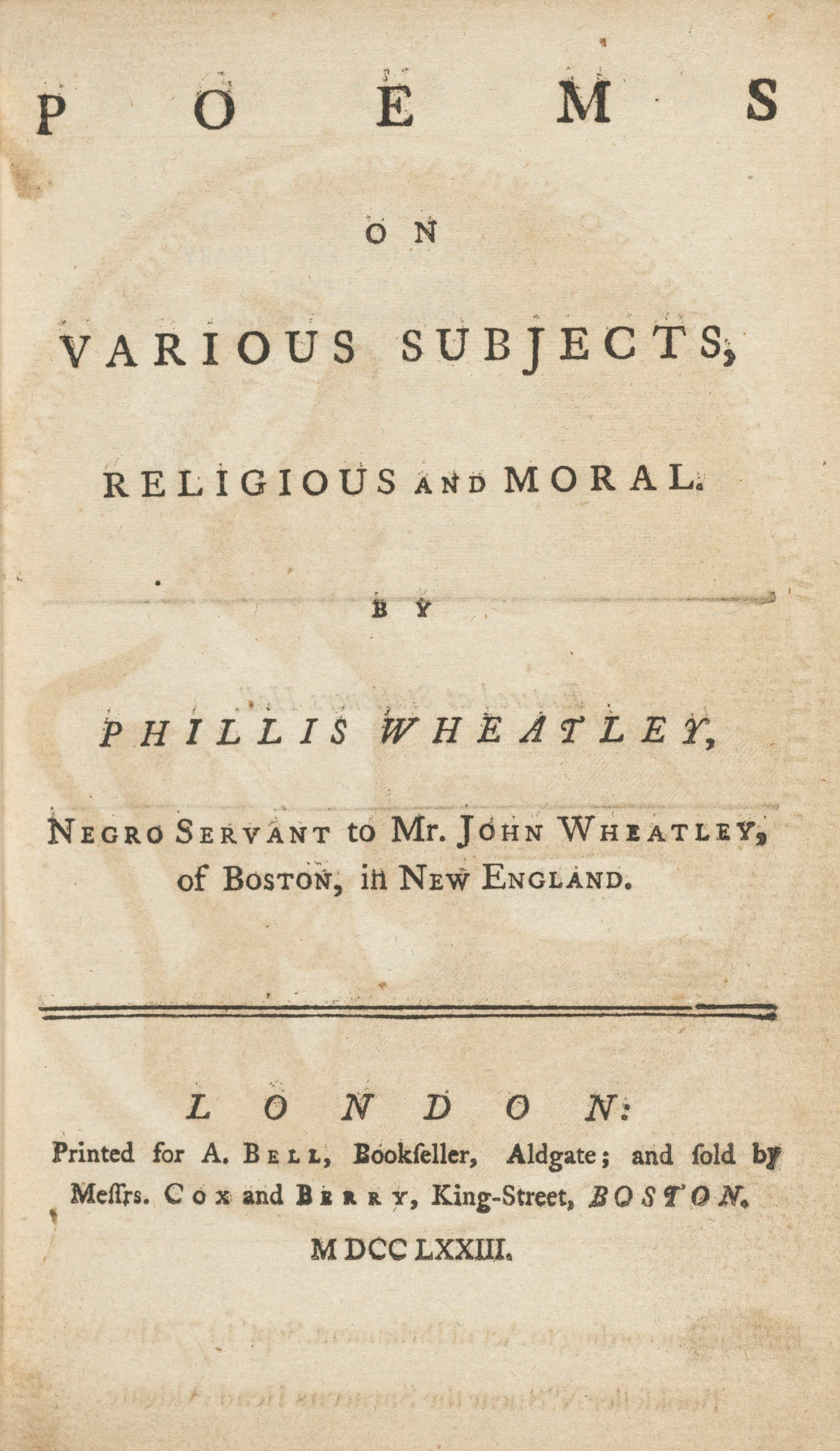

On a bright morning in the spring of 1772, a young African woman by the name of Phyllis Wheatley walked into the Boston courthouse to undergo an oral examination, surely one of the oddest oral exams on record. This test, this ordeal, this procedure was organized so as to assess whether it was natural for a Black woman to read and to write? Do Black women and men have the capacity to reason? Can we publish scholarly literature? The bottom line, fundamental question was how could a Black woman who was limited to doing kitchen table ethics obtain knowledge commensurate to a classical education only available to young white men of Harvard...There gathered in a semicircle, sat eighteen of Boston's most notable citizens. Among them was the Rev. Charles Chauncey, pastor of the Tenth Congregational Church, John Erving a prominent Boston merchant, and John Hancock...At the center of the circle sat His Excellency, Thomas Hutchinson, governor of the colony, with Andrew Oliver, his lieutenant governor, close by his side...This group that later defined itself as "the most respectable characters of Boston" had assembled to question closely Phyllis Wheatley's book, the first book written and published by a Black woman in America. We can only speculate on the nature of the questions posed to the young writer...We do not know the details of the questions. We do know, however, that Phyllis Wheatley's responses were more than sufficient to prompt this blue-ribbon jury of Boston's finest to compose, to sign and to publish an open letter to the public declaring that based on the results of the oral examination of Phyllis Wheatley that Black women can think, that Black women do have the capacity to reason, that Black women can write and publish scholarly literature.

Rev. Dr. Cannon writing about Phyllis Wheatley struck me as I searched through her words for connections between various sermons and lectures. Again and again, Cannon used the exact same verbiage describing that fateful oral examination of Phyllis Wheatley that determined that Black women were not just capable of thought, but of high intelligence as well. I found it first in her sermon “Keeping the Faith, Disturbing the Peace” where she used Wheatley’s story to describe how Christianity, in an attempt to create authenticity, must unmask and untangle the problems of its past.

It is in this lecture where I first found the idea of lived experiences as sacred texts. Cannon states explicitly that the examples she has prepared, including the life of Phyllis Wheatley, “exemplify Black women’s lives as sacred texts.” After a description of Wheatley is given, Cannon then uses her story to illustrate the topic at hand of “keeping the faith, disturbing the peace.” Cannon relates this story of Wheatley to her sermon’s greater call to action, to attempt to make a difference in the world of academia, which still attempts to force Black men and women to prove themselves worthy, intelligent, and capable, as Phyllis Wheatley did in Boston in 1772.

Rev. Dr. Cannon uses this life story again in her sermon “Calling for the Order of the Day”. Here, she repeats the story of Phyllis Wheatley, but the application of this lived sacred text is different. The focus of this lecture is instead on the way that Wheatley’s life and works exemplify the womanist need to center the lives of African American women in order to, as she says in the sermon, “imagine justice-making work in our future.” In this call to action, Rev. Cannon asks for genuine inclusivity in both the Church and congregation in the way that knowledge of the past is approached.

In “Catching Our Moral Breath,” Rev. Dr. Cannon returns to the idea of African American lives being used as sacred texts. She uses both her life and the life of Phyllis Wheatley to promote the lesson to be learned: that progress cannot continue with the omission of some experiences. Arguing that omitting some women from education and non-genuine inclusivity will lead to unbalanced, incomplete, and distorted views of the past and future.

The usage of Phyllis Wheatley’s story as a sacred text is in general, a prime example of womanist theology at work. Rev. Cannon “walks the walk” so to speak by using the early Bostonian’s life to demonstrate in the modern day what womanist ideals are and how they can be applied. Using Wheatley’s life as a sacred text pushes an African American woman to the forefront, where she historically has not been allowed to be, explains her life from a womanist point of view and serves as an example to others of how they can elevate other African Americans to the same place.

Rev. Cannon utilizes Phyllis Wheatley’s story in the same way that she uses scripture from the Bible. Using her story of historical adversity is no different than teaching with stories like David and Goliath or the Good Samaritan. In the end, their purpose is to speak to a larger story and lesson at hand and apply them to the lives of the congregation. Rev. Cannon takes the womanist approach to this by using an African American woman to center that perspective.

Rev. Cannon uses the life of Phyllis Wheatley to not just answer the questions of womanism or to teach congregations the trajectory of their futures, but to demonstrate that Black women’s lives are worthy of being sacred texts.

--Matty Marrow is a History major at Pennsylvania State University and PHS's BKBB Archives Intern for Spring 2023.