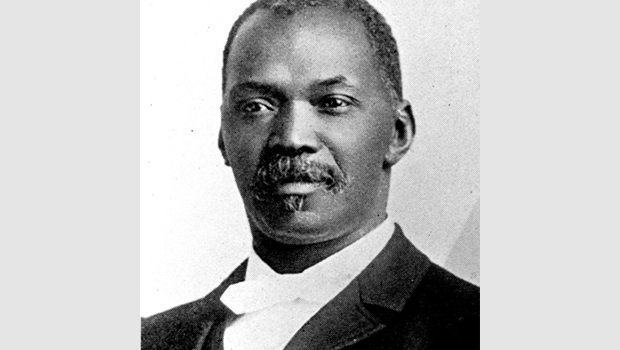

African American Leaders: Rev. Daniel Jackson Sanders

--by Matty Marrow

Daniel Jackson Sanders, of Winnsboro, South Carolina, was a devout Presbyterian, a champion for education, and dedicated to the advancement of his race. His story of unlikely success began with birth on February 15th, 1847, into slavery. He was owned by the same man as his mother, Thomas Hall, a methodist minister. Upon Hall’s death, they were sold to his father’s owner, Major Samuel Barkley—a Presbyterian minister—reuniting the family for a period. During this time, Sanders was permitted to learn the Barkleys’ trade of shoemaking. He proved more than adept at the skill and from the ages of 9-16, he quickly advanced through his apprenticeship.

At the same time, Sanders began to learn to read. Who exactly taught him is unknown, but he did learn a few letters from his “favored associates.” During this time, everything with printed letters became his textbooks as he used signs and advertisements to study. He eventually received two books, one of them being a spelling book. By Emancipation in 1865, Sanders could spell and read a little.

In 1866, he left his hometown for Chester, South Carolina. He continued to work as a shoemaker and managed to find a tutor in a white man, W.B. Knox. Sanders continued his education through Knox until he eventually had prepared enough to enroll in Brainerd Institute, which he graduated from in 1870. Around this time, he was also ordained by the Fairfield Presbytery as a minister. Sanders again continued his studies, joining the junior class of the Western Theological Seminary in Allegheny County, Pa. He graduated in 1874 as the only non-white member of the 40-person class.

After Seminary, Sanders served as the pastor of the Chestnut Presbyterian Church in Wilmington, North Carolina for 15 years. During this time, he was also awarded honorary degrees from Lincoln University in Chester County, Pennsylvania for a Master of Arts and a Doctor of Divinity.

In 1879, Sanders began his newspaper, the Africo-American Presbyterian; dedicated to local, national, and Presbyterian news. Sanders' goal for the newspaper was to inspire both African Americans and the Presbyterian Church as a whole.

Eventually he served for the Board of Missions for Freedmen raising funds abroad in Europe for an education fund. After some time in Scotland, he helped to raise $6,000 for an African Scholarship fund at the formerly named Biddle University, now Johnson C. Smith University (JCSU).

Rev. Sanders rose to the presidency of Biddle University in 1891. Upon Sanders' appointment, 3 of 4 white professors resigned, which did allow for three more African Americans to move to professor roles. Despite some original misgivings, Rev. Sanders served honorably as the president until his death. During his tenure, the first intercollegiate football game between non-white schools was played in 1892. He revitalized the facilities of the school, working alongside men like Booker T. Washington and Andrew Carnegie, to secure the future of the school’s library and ensure its growth. Rev. Sanders dedicated himself to the development of both Biddle University and the young men that walked through its doors. The prestigious nickname of “Zeus” was given to him by his students which demonstrates the impact that he had on them during his time as president.

The life of Reverend Daniel Jackson Sanders is a testament to the long-standing history of African American leaders in the Presbyterian Church. Sanders was a pioneer in his own right despite the obstacles he faced. He contributed greatly to the education of individual students during his time as President at JCSU and to the education of Black Presbyterians everywhere with the Africo-American Presbyterian.

By no means, was he the most radical of African American man of his time, but he did wholeheartedly believe in the advancement of African Americans beyond. Unfortunately, Sanders' views and work were belittled by many of the white men who interpreted his work, in both life and death. These interpretations of his work can be most clearly seen in his obituaries, where most of the information of his influential life can be found.

These obituaries solely focused on his abilities in working with white men. The Charlotte Evening News stated, “If Dr. Sanders ever uttered a word about the inequality of the law, the oppression of the colored race, the miscarriage of justice, the robbery of the race of suffrage, and all that, we have no recollection of it. He may have felt these things in his heart, but he was too wise to rebel against conditions that he could not alter or amend” This sentiment is repeated throughout the writings about Rev. Sanders from white authors: that he was a man that was content in his place in the country and world and if he wasn’t, he was at least smart enough to not speak on it.

This, however, proves to be a lie because Reverend Sanders did speak on his place in the world, repeatedly. He spoke frequently in his newspaper, the Africo-American, and in others about the advancements of African Americans and the ways that the country and church could better serve them as they lifted themselves from where slavery left them. In his writing, “The Rightful Place of the Negro” Rev. Sanders perfectly sums up his own thinking with the words: “Standing here today firmly on both feet with 30 years between us and slavery, and its abolishment, proclaimed by the immortal Lincoln, and its shackles broken by the heroes of the grand cause of human liberty, living and dead, let us face boldly to the future, trust In god and do the right, and put forth out continued and best efforts to realize all that is implied in our rightful status in the republic”

Those are the words of a man who did utter a word about the inequality of the law and who did believe that the oppression suffered by his race was unjust. It is willful ignorance of those who wrote obituaries such as that from the Charlotte Evening News to believe anything else.

My purpose with this post then was to attempt to undo some of the damage done by the white contemporaries of Rev. Sanders and give his story and legacy the light that it deserves. For a man so influential and so beloved in his time, it is almost unbelievable that so little exists on his early life and his work. Ultimately, the best way to summarize Sanders' work, legacy, and hope for the future of African Americans is with his own words as he states in The Evangelist in January 1900, “The future will be determined largely by this. Those white friends who torment themselves over trying to do something with the negro might contribute to this brighter future by coming to regard him as a brother man and do something for him”

--Matty Marrow is a History major at Pennsylvania State University and PHS's BKBB Archives Intern for Spring 2023.