We Speak for Ourselves: What Samuel Cornish Learned from John Gloucester

--by Kenneth J. Ross

Two hundred years ago, in 1819, the Presbytery of Philadelphia launched Samuel Eli Cornish (1795–1858) into a remarkable career as minister, evangelist, missionary, publisher, and social reformer.[i] Following a rigorous two-year program of intellectual, practical, and theological training, Cornish became the first African-American preacher to be licensed by the presbytery, making him one of the first African-American ministers in the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.

For a year, he preached among slaves and freedmen in eastern Maryland and his native Delaware before moving to New York City, where he was ordained as an urban missionary to New York’s growing black population. That same year Cornish organized the First Colored Presbyterian Church of New York City and served as its pastor while continuing his missionary work. He founded Freedom’s Journal, the first black-owned and operated newspaper in America, in 1827.

Over the next two decades, Cornish would go on to found two more congregations (in Newark, 1843; Manhattan, 1845), two more newspapers (1829 and 1837), and help co-found the American Anti-Slavery Society (1840)—all while lending his name, support, and editorial voice to nearly a dozen regional and national missionary, anti-slavery, educational, and moral reform societies. His mentor John Gloucester (1776–1822) had told him, “Better to wear out than to rust out,” a charge Cornish took to heart.

While Samuel Cornish spent most of his career in New York, he spent his formative years, 1815 to 1822, in Philadelphia. In this first of a two-part series, we will look at Cornish’s arrival in Philadelphia, his mentor relationship with John Gloucester, the powerful influence of the city’s African-American churches, and his request to become a candidate for the Presbyterian ministry in 1817. Part 2 will trace Cornish’s formal two-year professional training, his one-year probationary period, and his departure for New York in 1822.

A Sanctuary City

Philadelphia in the first decades of the nineteenth century was the home of the largest free black population in the United States and a rapidly growing one. According to the census, there were 2,078 African-Americans in the city in 1790 and 12,110 by 1820. Because of Philadelphia’s location, many of the newcomers were recently emancipated slaves from Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey. For them the city meant safety, an opportunity for work and education, and the sympathetic support of an established free black community.

The Free African Society, organized in 1787 and funded by a wide circle of black and white subscribers, offered a diverse social service program designed to help its members work, secure housing, learn new skills, establish a family, and “improve their habits.” The FAS was the largest of a network of “institutions of uplift” designed to equip rural black newcomers for urban living by fostering literacy and encouraging industry. According to witnesses, by the turn of the century the African-American community in Philadelphia was more self-sufficient than the general population.

Cornish joined this tide of immigration. He was born to free parents in southern Delaware, where black emancipation had been increasing since the close of the Revolutionary War. Although he received a basic literacy and religious education, arrangements were made to send him to the bustling metropolis of Philadelphia, where his talent, curiosity, and ambition could be rewarded.

The Central Place of the Church

Cornish may have reached the city by 1815, when he would have been 19 or 20. By 1815, the Cedar Ward on the southwest side of the city, and the adjoining township of Moyamensing, were the heart of the Philadelphia black community. The African-American population was moving in increasing numbers into that district because of its affordable housing, accessible schools, and strong black churches.

The churches were the most supportive institutions a new immigrant might hope to find. The oldest, the African Episcopal Church of Saint Thomas, developed out of the religious programing of the Free African Society, opened in 1794 under the leadership of Absalom Jones (1746–1818). Almost in tandem, Richard Allen (1760–1831) opened the Bethel African Methodist Church three blocks farther south. Both churches seamlessly combined their core mission of worship and consolation with ministries of education, uplift, aid, and mutual correction. Both buildings were deliberately owned and managed exclusively by their black members.

The churches were also the institutional foundation of a powerful black movement to abolish slavery, encourage African-American educators, demonstrate the equality of blacks and whites, and advocate for the full inclusion of African-Americans in the American political process. Richard Allen in particular insisted that African-Americans should be proud of their ancient heritage, as well as their recent trials and progress. Black Philadelphians needed their own institutions, free from white control, to define for themselves the meaning of liberty, equality, and citizenship.

The First African Presbyterian Church

In the midst of this ferment of African-American identity and community building, white Philadelphia Presbyterians organized a twenty-person African-American mission in Moyamensing in 1807. Following the lead of the city's successful black churches, they searched for a black minister. Their attention was drawn quickly to John Gloucester, a former slave working as a missionary among the Cherokee Nation in Tennessee. Gloucester was a striking figure—tall and athletic with a deep and musical voice—and by that time had been “well instructed in the doctrines of the Presbyterian faith” and “for several years engaged in the study of literature and theology.” For the next three years, 1807 through 1810, Gloucester worked roughly half time as an evangelist in the Cedar Ward and preacher to the African Presbyterian mission while also completing his ministerial training in east Tennessee, 250 miles away. Despite these awkward arrangements, the congregation grew. In 1810, Gloucester was ordained and transferred to Philadelphia where he, in the language of the era, “took his seat in presbytery.” He was 33.

Under Gloucester’s care the congregation prospered. In 1811, the presbytery organized it as the First African Presbyterian Church and soon dedicated a “substantial” brick church in Moyamensing. Gloucester established a day school for children, a temperance society, and adult catechetical classes patterned on his former work as a missionary, but he surely learned from Richard Allen, Absalom Jones, and many others that a community of traumatized refugees, recently freed slaves, and poor urban workers needed a more holistic mission. Forming alliances with black churches and white-funded charities, he quickly adapted.

The Making of a Presbyterian

As Samuel Cornish sought support, made connections, and networked to pursue higher education in the Athens of America, he was drawn into Philadelphia’s rapidly changing social, religious, and political mix. It would appear that he associated himself early with Gloucester and the Presbyterians, rather than with the more numerous Methodists or more elite Episcopalians. It’s possible that he brought a preference for Presbyterianism with him from Delaware, or he may have acquired it from Gloucester. We know that Gloucester was recruited by both traditions and refused them. He and Cornish may have spoken about this.

Gloucester’s reasons may have been theological. From his Presbyterian training he may have disagreed in principle with various aspects of Wesleyanism and Episcopalianism. There was always a friendly but insistent competition among the denominations of the era that required church leaders in every tradition to be public and clear about their differences without becoming aggressive or preventing cooperative action. Cornish would have witnessed this first hand.

John Gloucester, circa 1805. Pearl ID: 5272

John Gloucester, circa 1805. Pearl ID: 5272Gloucester may have also preferred Presbyterian polity. Its non-hierarchical structure allowed every congregation to elect its leaders and to ordain its elders without the consent of a bishop. White episcopal control over ordination had been a constant frustration for the black churches of Philadelphia. Jones was not ordained a deacon until 1795 and was not ordained a priest until 1802—eight years after he assumed leadership at St. Thomas. Allen qualified as a Methodist preacher in 1784, but was not ordained a deacon until 1799—five years after he assumed leadership at the Bethel church. Gloucester, by contrast, was a full member of his presbytery and could provide his congregation with the sacraments the day he arrived.

Pragmatically, we know that Gloucester also provided Cornish access to excellent teachers and libraries through his local presbytery connections. Collectively, the Presbyterian ministers of Philadelphia were some of the most accomplished of the denomination—scholars, authors, and educators with national reputations. The largest theological collection in the region could be found within easy walking distance in the library of Rev. Dr. James P. Wilson, minister at the First Presbyterian Church.

We may assume that Cornish took advantage of such resources. On October 21, 1817, with John Gloucester in attendance, Rev. Dr. Ezra Stiles Ely presented Cornish to the presbytery to be taken under care as a candidate for ministry. The presbytery acknowledged that Cornish had not graduated from college, but allowed they had the traditional option to train him themselves, a process that usually took two years. Cornish was immediately given two major assignments to complete, each requiring strong research and writing skills. His “trials for ordination,” as they were called, had begun.

For the next three years Cornish will continue to work closely with Gloucester and the First African Presbyterian Church, but he will be drawn into the wider world of American Presbyterianism, the strengthening Christian antislavery movement, and a church conflict over “colonization" — an alarming movement to “repatriate” African-Americans to West Africa. Cornish’s ministry would be shaped permanently by these struggles. We will look at these developments in Part 2.

--

The Reverend Kenneth J. Ross was born and raised in the Philadelphia area. He is a graduate of Lafayette College, Andover Newton Theological School, and Princeton Theological Seminary. A member of the PHS staff from 1990 to 2006, he is now retired.

Further Reading:William T. Catto, A Semi-Centenary Discourse, Delivered in the First African Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia on the Fourth Sabbath of May, 1857, Philadelphia: Joseph Wilson, 1857.

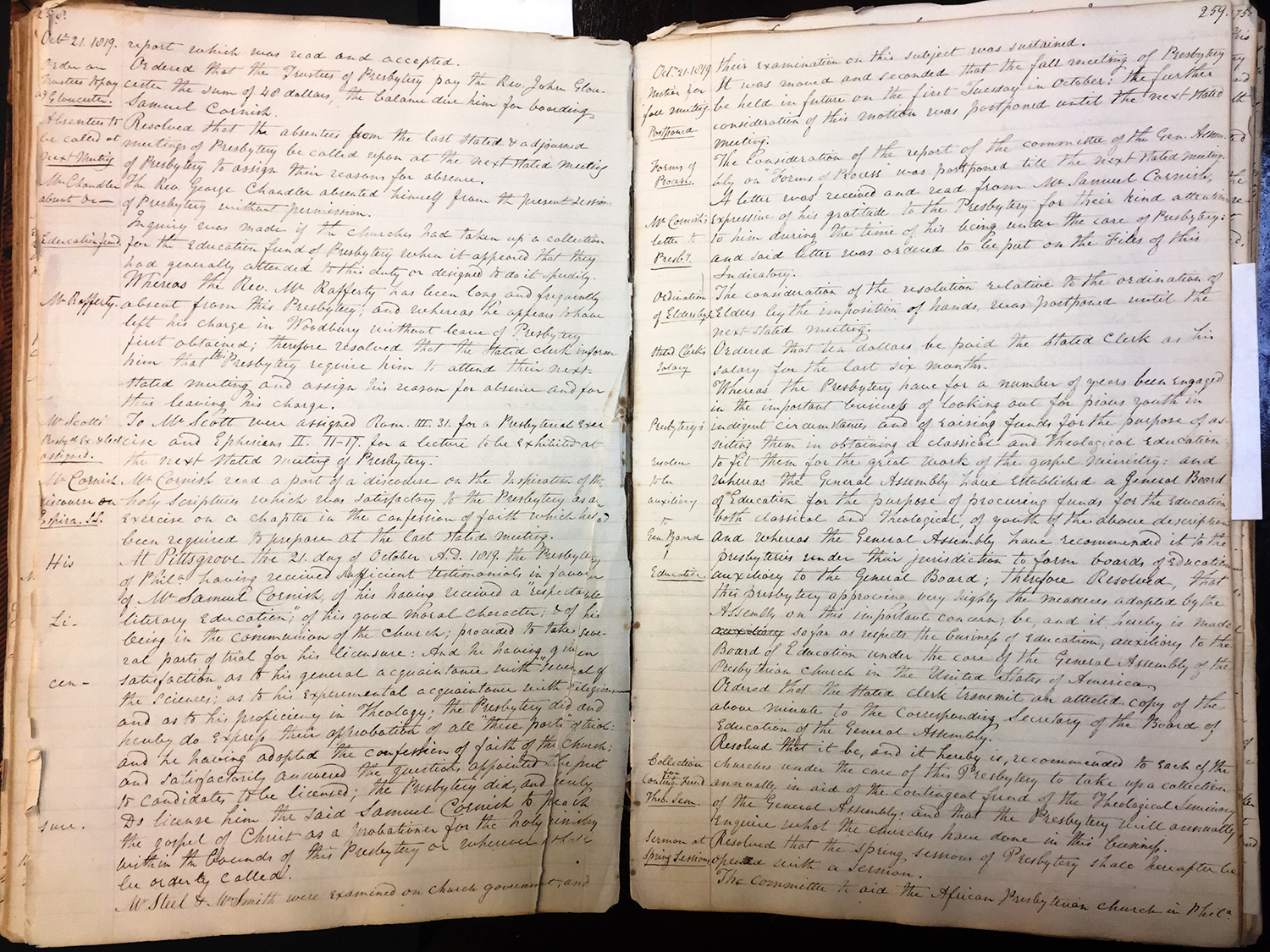

Gary B. Nash, Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720–1840. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988.[i] “At Pittsgrove the 21. day of October A.D. 1819, the Presbytery of Phila. having received sufficient testimonials in favor of Mr. Samuel Cornish, of his having received a “respectable literary education;” of his good moral character; & of his being in the communion of the church; proceeded to take several part of trial for his licensure. And he having given satisfaction as to his general acquaintance with “several of the sciences;” as to his experimental acquaintance with religion; and as to his proficiency in Theology; the Presbytery did and hereby do express their approbation of all “these parts” of trial; and he having adopted the confession of faith of the church; and satisfactorily answered the questions appointed to be put to candidates to be licensed; the Presbytery did, and hereby Do license him the said Samuel Cornish to preach the gospel of Christ as a probationer for the holy ministry within the bounds of this Presbytery or wherever that he be orderly called.” Transcription from "Minutes of the Presbytery of Philadelphia," October 21, 1819, p. 258.