The Things She Saved: Images and Objects in Missionary Women's Archives

--by Deanna Ferree Womack

Church archives can be treasure troves for research on missions and Christianity around the globe. I found this to be true when working on my first book, Protestants, Gender and the Arab Renaissance in Late Ottoman Syria.

Missionary Treasure Troves

The “treasures” that I sought when researching Protestantism in Syria were mainly written documents like letters exchanged between Arab Protestants and American missionaries. Or handwritten mission employee lists bearing the full names of Syrian Biblewomen (women preachers) whose identities were left out of published reports. On occasion, including a recent visit to the Presbyterian Historical Society, I found images that put faces to women’s names, like a photo of Syrian nurse Afifa Saba at the American Syria Mission’s tuberculosis sanatorium that she supervised during World War I.

In the same tuberculosis hospital files is a tiny stamp from the Syria Anti-Tuberculosis Society. It tells the story of Syrian Muslims and Christians who joined together after the war to address rising TB cases in the region. By selling these stamps, Syrians funded the treatment of patients at the mission hospital and eventually started a Syrian-run sanatorium. With the words “Light and Relief” inscribed in Arabic and French, the stamp is a reminder of the French Mandate over Syria and Lebanon in the post-WWI period. Most striking of all is the figure of a woman lifting a light in one hand and holding the arm of a TB patient in the other. Next to the emaciated patient, the woman is a symbol of strength, representing nurses like Afifa Saba who were essential to health care in Syria.

Ephemeral items like this stamp are rare in archives that mainly preserve official mission society records. But images and other material objects appear more frequently in missionaries’ personal papers, especially the papers of women. For example, during my recent visit to PHS I came across so many tangible artifacts in the collections of missionary women in the Middle East and South Asia that it prompted a new question: Beyond written records, what more can we learn by studying the images and objects that missionary women saved?

Snapshots of History

Like the anti-TB stamp, some materials in missionary women’s archives expand our knowledge of a particular region or era of history. At PHS, these included scrapbooks, portraits of missionaries in local garb, cultural artifacts, and documents commemorating significant political events. I found all four types of items in the papers of Kate Alexander Hill, a missionary of the Women’s Board of the United Presbyterian Church of North America. Hill directed a number of mission hospitals in India from 1896 to 1943. One photograph shows her wearing a sari she received from the Indian nurses. Other pictures attest that Hill usually wore western clothing, but the sari photo indicates the close relationship she had with local people after decades working in India.

Hill’s scrapbooks represent this work with photos of mission hospital buildings and staff. Other albums show how she spent her time on furlough:

• photos of Hill attending women’s missionary meetings in the US,

• pages of newspaper announcements about her many lectures and fundraising presentations, and

• postcards and colonial photography from a Holy Land tour en route to the US.

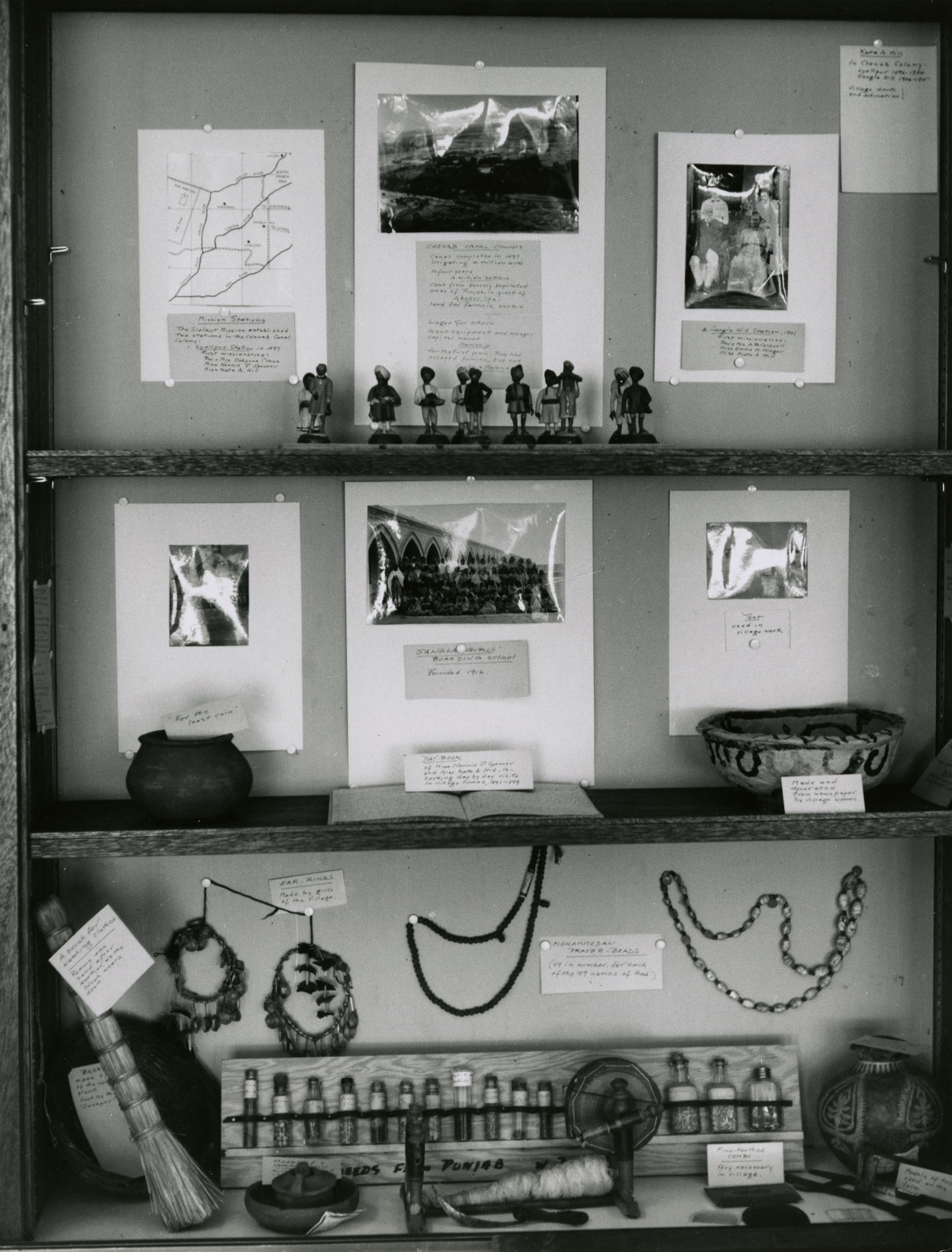

Hill was one of many missionaries who toured the Middle East in the early twentieth century and collected colonial photographs (photos of colonized non-western peoples purporting to show typical ways of life and dress). Such snapshots, like the two shown above, were staged by entrepreneurial photographers and usually Orientalized the subjects (highlighting their differences from western cultural norms). The images and scrapbooks Hill kept also indicate that she collected Indian cultural artifacts and shared them with church people back home in what the newspapers called exhibitions of “India Curios.” These included Muslim prayer beads, jars of seeds from the Punjab, Indian women’s handiwork, pottery, figurines, and various items of men’s and women’s clothing. The result was a small traveling museum. Hill’s museum of “curiosities” shows how missionaries drew supporters by presenting Asian cultures as strange and exotic. Yet such displays also informed American church-goers about the lives and histories of people they would otherwise never come to know.

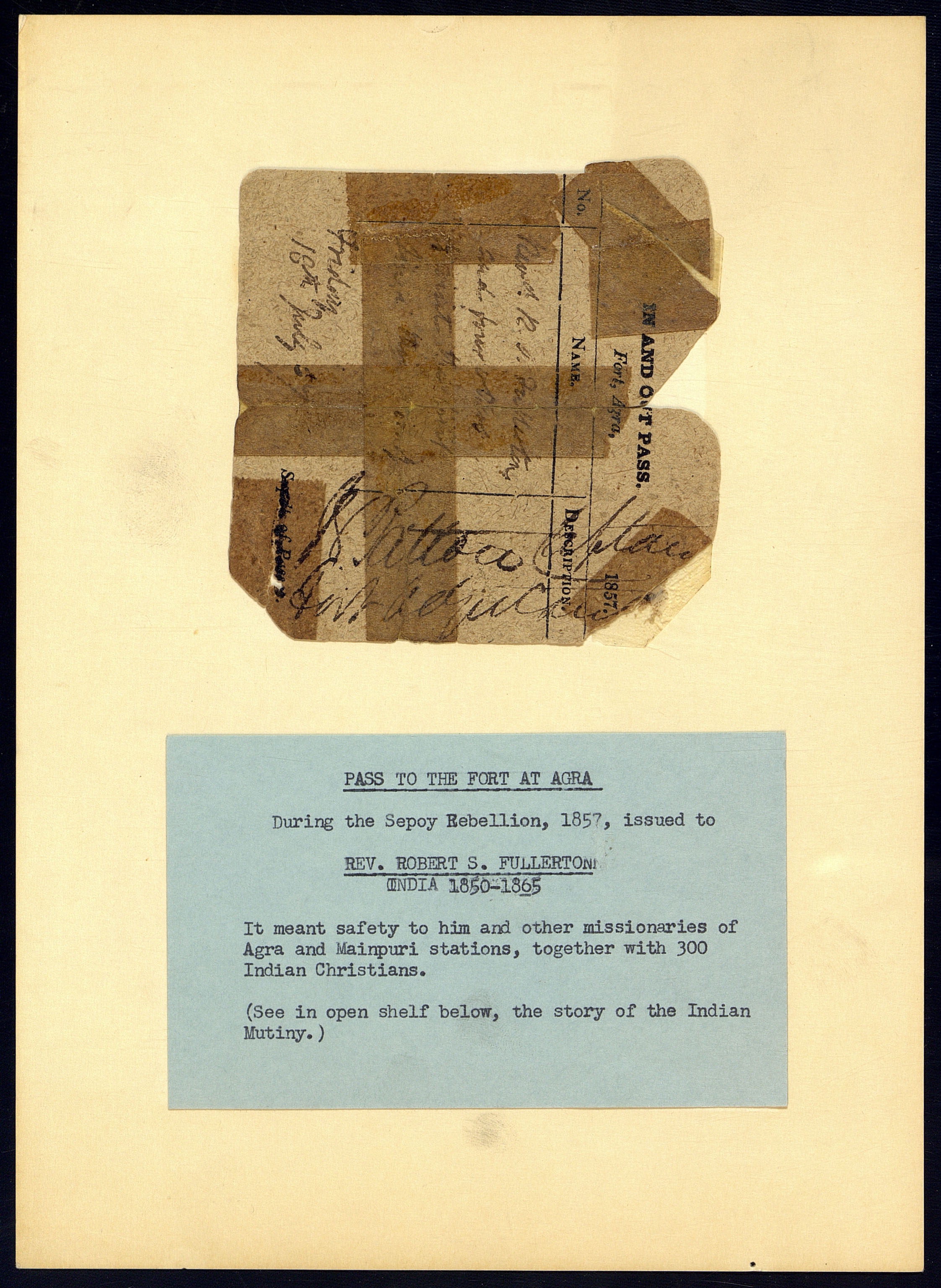

One final item in Hill’s curios display documented the long history of Presbyterian work in India, facilitated by the British colonial presence there: a pass to the Agra Fort issued to missionary Robert Fullerton in 1857. Agra is the site of the famous Taj Mahal, and the nearby fort was the residence of the Mugal Emperors, a Muslim dynasty that ruled much of India until 1857. That year the British suppressed a major uprising (known as the “Indian Mutiny” or the “first war of Indian independence,” depending on one’s perspective). Fullerton acquired the pass and fled to the fort during the fighting. According to Hill’s display, “It meant safety to him and other missionaries of Agra and Mainpuri stations, together with 300 Indian Christians.”

Personal Mementos

Still other items in women’s missionary archives are personal in nature, and for that reason they are easily passed over by researchers looking for a more official history. These mundane mementos, however, show an important side of missionary women’s lives. At PHS, such items included:

• Scraps of dress fabric and buttons that Kate Hill sent home with descriptions of her shopping trips in Indian markets.

• Inspirational quotes, recipes, and home remedies that Anna Thompson (in Egypt) copied onto scraps of paper or cut out of magazines.

• Flowers and leaves that Belle Hawkes (in Persia) pressed between the pages of diaries or painted.

• Snapshots of pets, like the cats who lived with Hawkes in the mission field.

These materials that missionary women saved tell important stories too: of a quirky sense of humor, time taken to appreciate nature, the love of animals, or hobbies unrelated to official mission business. So often scholars and church leaders use textual evidence to glorify missionary altruism or to critique missionary biases. More mundane pieces of history, like these women’s keepsakes, remind us of the human side of figures that are otherwise just subjects for historical scrutiny.

--Deanna Ferree Womack is Assistant Professor of History of Religions and Multifaith Relations at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology and a minister in the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). She is the author of Protestants, Gender and the Arab Renaissance in Late Ottoman Syria (Edinburgh University Press, 2019) and Neighbors: Christians and Muslims Building Community (Westminster John Knox Press, 2020). Her 2019 research at PHS was supported by a Gerda Henkel Foundation Grant.