Billy Sunday and the 1918 Flu Pandemic

During a time when Presbyterians and all people who gather in groups of two or more are prayerfully considering how to commune, whether to cancel church, how to obtain individually wrapped communion servings, and whether any of those changes comport with proper worship, we reflect on when the evangelist Billy Sunday was shut down by the Aldermen of Providence, Rhode Island, during the flu pandemic of 1918.

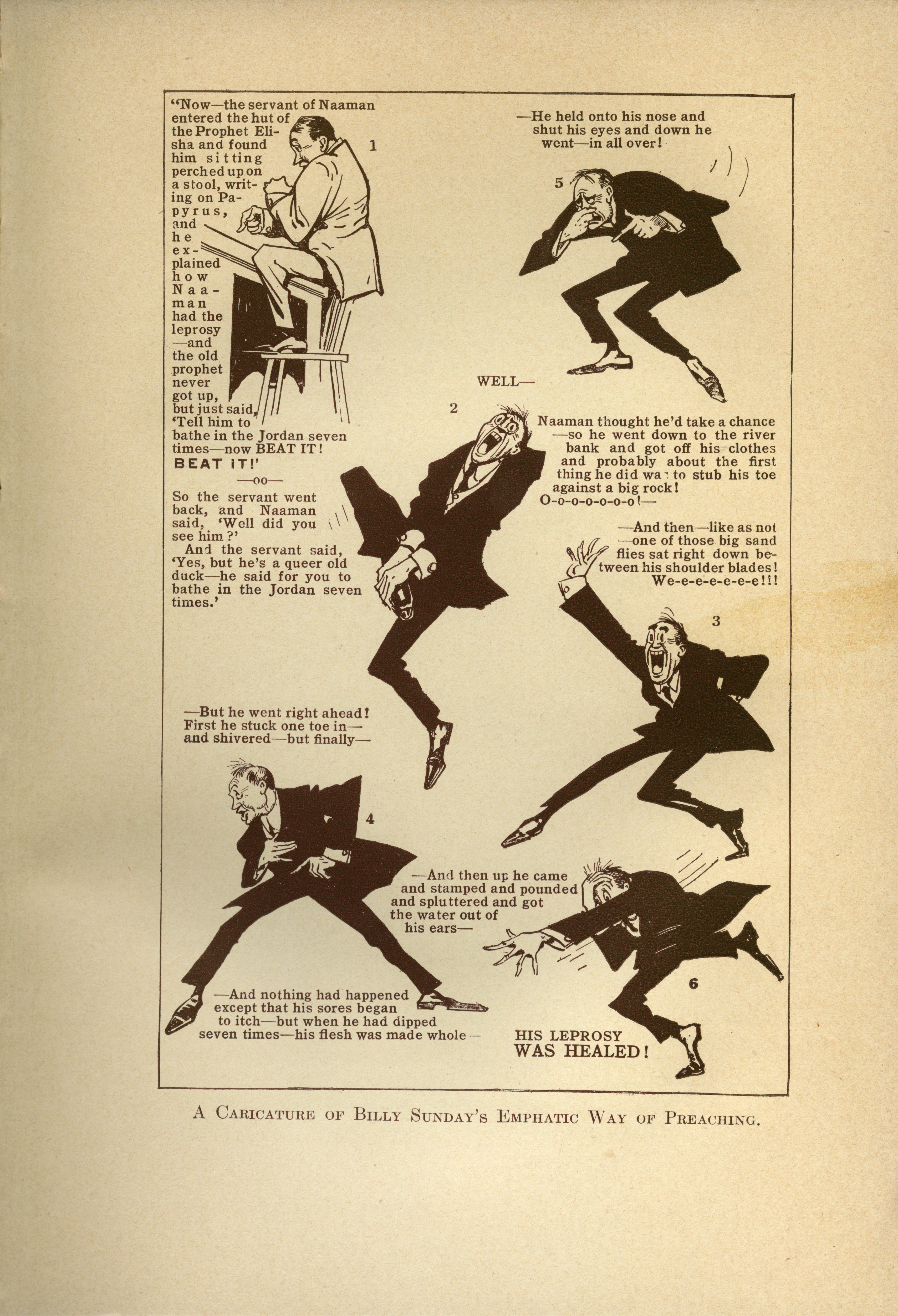

Billy Sunday was a Presbyterian dyed in the wool. Born in Pittsburgh, trained at McCormick Seminary, ordained in Chicago, and recruited by J. Wilbur Chapman as an evangelist, he was so wildly successful as a campaigner against whiskey (and later, against the Kaiser) that the 1918 PCUSA General Assembly was moved to put a salary cap on evangelists because of him. In the prior three years Sunday had made $600,000.

In March of 1918 the first unusual flu cases in the United States were reported among soldiers in Fort Riley, Kansas. From March 10 to May 28 of that year, Billy Sunday held a series of revivals in Chicago against the "booze interests," campaigning to get prohibition on the statewide ballot that April. The evangelist would claim to the Chicago Tribune that he converted 49,165 "trail-hitters" -- it's likely that this represented a fraction of the hundreds of thousands who entered the Sunday Tabernacle in the first spring of the flu. In Chicago, the flu uniquely targeted younger adults: deaths among people aged 21 to 40 quintupled those among people aged 41 to 60. More than 8,000 people would die of the flu in Chicago.

In the fall, Sunday set up the Tabernacle in Providence, Rhode Island, hosting seventy meetings in September and October. By this point both the war in Europe and the so-called "Spanish flu" were in public consciousness. As Sunday exhorted his congregants to "pray down" both the flu and "the Hun," newspapers reported numbers of them collapsing in the aisles.

For his part, Sunday bowed to civil authority and the exigencies of an unprecedented moment: "It is up to us to hope and pray."

Some 6,000 residents of Providence would be sickened that year, and by the end of the outbreak in 1920 more than 800 would die. The Providence Aldermen shut down public gatherings in October, effectively halting Sunday's evangelism. For his part, Sunday bowed to civil authority and the exigencies of an unprecedented moment: "It is up to us to hope and pray. We are always willing to help anything that is for the public good and do it cheerfully. There is nothing drastic in the order, and it is issued in an attempt to stamp out this epidemic." The Methodist newspaper Christian Advocate mocked Sunday. "We are not sure but that influenza is preaching to more people than Billy Sunday ever did":

Sunday's ministry would decline at least in part due to the rapid growth in popularity of worship at a distance -- radio created the first broadcast evangelists, the institutional church would support broadcasting, and the most successful of them, another preacher named Billy, would turn around and gather tens of thousands of people in one place in person.