Sea to Shining Sea: The Story of U.S. Navy Chaplain John E. Johnson

--by Merwyn S. Johnson

Before he sailed the world’s great oceans as a career U.S. Navy chaplain, my father John E. (“Johnny”) Johnson surveyed the “amber waves of grain” in Iowa, the ancestral home where he spent his summers as a youth. Whether on land or on ship, the seas gave him a wide horizon for his entire life. Navigating them for almost 100 years, May 2, 1899 to November 17, 1998, he immersed himself in the events and sweeping changes of 20th century America.

Military service was highly valued by my father and countless others of his generation. The records of the Presbyterian Historical Society (PHS) reflect his life and story well, along with other Presbyterian chaplains from the Army, Navy, and Air Force—especially those who served our nation during World War II.

Young John graduated from high school in South St. Louis, MO, where his father was minister at the Winnebago Presbyterian Church. He joined the U.S. Navy Reserve in 1918 just as World War I wound down and continued his ties with the Navy by accepting a call to the Chaplains Corps after college (Dubuque) and seminary (Princeton). The Presbytery of St. Louis ordained him to ministry in January 1924, and he began his service as a chaplain in May. His various studies gave him a strong literary turn in all his speaking and writing.

The Navy chaplain operates within tight specifications. The officers and sailors (or marines) are part of a team working together, often in close quarters, with expensive, high-tech machinery, to do the task at hand—steer the ship, fly the plane, fire the big gun, execute a tight maneuver, land in hostile terrain, secure a tough objective, or supply the unit with food and ammunition. As a military unit, the team has to constantly prepare for battle, do battle on call, and pick up the pieces from any battle aftermath. Such conflict entails a willingness to kill and be killed in defense of your country, your unit, and your buddies.

Military teamwork relies utterly on personal character, integrity, and courage, as well as the ability to lead others or follow when needed. Soldiers, sailors, and marines cannot avoid facing tough questions about the value of human life, the meaning of human death, and the exercise of power in geopolitical affairs. These matters all fall directly within the domain of the military chaplain. Looking through a Christian lens, the chaplain will point to the value of living and dying in the constant presence of the living God—who lifts up our humanity by becoming one of us and who, on the cross, measures all other forms of power by how it serves those who have none. An indispensable corollary for the chaplain is the conviction that every human is created in the image of God, even the image of God restored in Jesus Christ—whether anyone else in the unit believes these things or not. That allows the chaplain to serve and care for every member of the team, regardless of religious preferences. Chaplain Johnny always remained grounded in God, the religious dimension, even when the Navy wanted to concentrate on morality training.

My father was one of seven chaplains commissioned by the Navy in 1924, in a year when the number of chaplains was only 83. His orientation to chaplaincy was decidedly low key: “The most impressive indoctrination I received in the Navy,” he said, “was on the fo’c’stle of my first ship [in 1924] when out of the wisdom of his years, the fatherly Chief Carpenter said to me: ‘In the Navy there are no disappointments, only pleasant surprises.’”

Chaplain Johnny doubtless absorbed The Navy Chaplain’s Manual (1918), by John B. Frazier, the first Navy Chief of Chaplains. This booklet was more prudential than task-specific but showed clearly where savvy chaplains fit on the Navy team. Other officers had prescribed times, places, duties, and authority to do their tasks, but as the Manual specifies on pages 8 and 9, “the chaplain has to ask for his time and ask for his place and ask for his opportunity. … [H]e must stand in no one’s way, and must conflict with no one’s duty. Instead of being able, as are other officers, to tell people what they ‘must do,’ he can only persuade, entreat, and exhort, oftentimes in the face of opposition and discouragement.”

Beginning in June 1924, Chaplain Johnny served the standard three-year apprenticeship aboard the troop ship U.S.S. Henderson. The executive officer took a dislike to him and persuaded others in the officers’ wardroom to shun him for a time. He endured, eventually broke the logjam, and found ways to reach the officers. He always connected well with the crew. Through the ship’s radio operator he became acquainted with a pretty redhead from Alabama, my mother, who would become his wife of 71 years.

“In the Navy there are no disappointments, only pleasant surprises.”

From 1924 to 1941 Chaplain Johnny served on five different ships, alternating between ship and shore duty. He spent a year getting further training in naval affairs, first at Newport, RI, and then Norfolk, VA. Though the clouds of economic depression (from 1929) and future war with Germany and Japan (from 1931) hung over America, it was still a peacetime Navy. Maximizing the sailors’ off-duty time, Chaplain Johnny coached a baseball team that won the fleet championship.

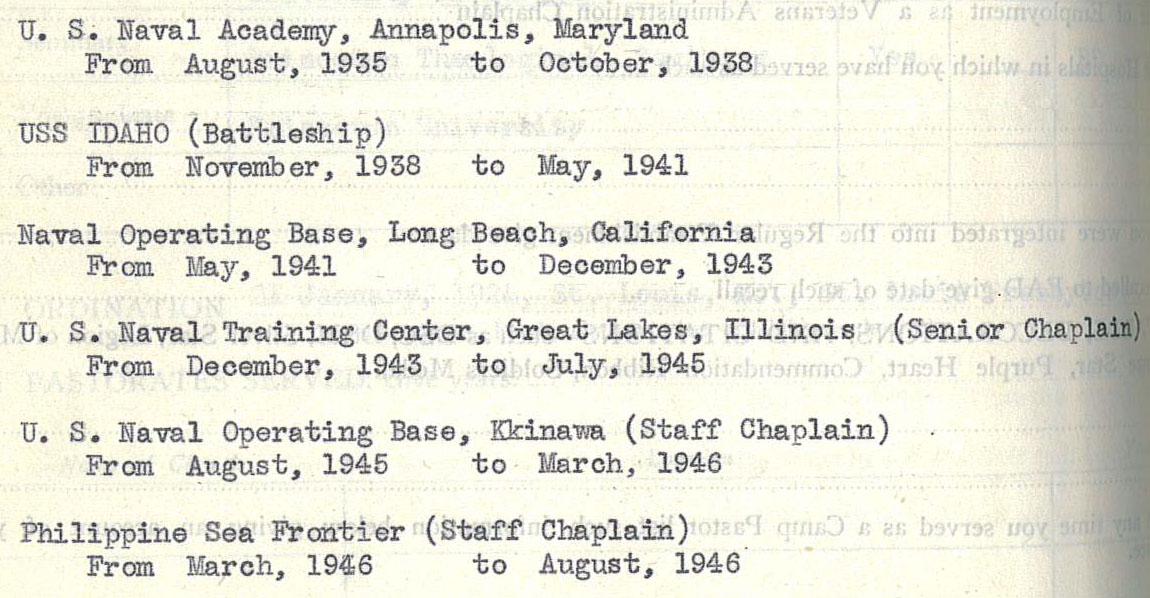

As a junior chaplain he served at the Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD (Aug 1935-Oct 1938) under the effective and well-regarded Chaplain William N. Thomas. This plum position challenged my father to elevate his preaching and counseling skills. While there he was promoted from Lieutenant to Lieutenant Commander.

Later, in 1939, he was aboard the battleship U.S.S. Idaho when it moved from Norfolk through the Panama Canal to the Pacific as a show of force to the Japanese. Part of his duty was to conduct worship services on a regular basis. On shore, that is usually in a chapel built for the purpose. Aboard ship, services take place wherever there is enough room. On the Idaho, Chaplain Johnny gathered his flock for worship on the fan tail and led the singing while he played a portable pump organ.

He left the Idaho in May 1941 and went ashore for duty at Long Beach, CA, where he soon received a promotion to full Commander. Long Beach had only recently been designated a Naval Operating Base, and Chaplain Johnny’s task was to create its Navy Relief program. He operated from an office in downtown Long Beach until the Base was fully built.

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, Long Beach was home port for the eight American battleships sunk or damaged that day. Chaplain Johnny was thrust into the war supporting the widows and families of the men aboard those ships. He did not create the Rosie the Riveter program (bringing women to fill positions vacated by men called into the war), but he championed the cause very early; a Life Magazine picture from early 1942 shows him with Pearl Harbor widows on their way to interviewing for manufacturing jobs. The proximity of Hollywood to Long Beach also brought a public spotlight to the Navy Relief activities. At one point, actor Ralph Bellamy donated a Pierce Arrow limousine and specified that only the chaplain should drive it. In June 1942 the Navy gave Chaplain Johnny a war-time promotion to Captain. In 1944 his alma mater, the University of Dubuque, awarded him an honorary doctorate for his work developing the Navy Relief program.

Chaplain Johnny’s next position was senior chaplain at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Illinois, on the banks of Lake Michigan (Dec 1943-July 1945). During the war years, over one million sailors passed through the station’s portals. The programs under his direction were many and the staff large. He published an article on his experiences there: “The Faith and Practice of the Raw Recruit.” The recruits, he observed, were thrown together as complete strangers from every conceivable background—city and farm, highly educated and illiterate, black and white, rich and poor, mostly Protestant (75% in 1944) but also Catholic (23%) and Jewish (1.7%), and the majority under 20 years of age. After training runs of 5 or 10 weeks, they left as close-knit units. Most recruits arrived with little interest in or knowledge of religion, but they would listen to a chaplain who had something to say and put it “low in the rack where they can get it.” Those were my father’s words of advice to me throughout my own professional life.

Under Chaplain Johnny, the chaplains at Great Lakes held separate worship services for Protestants, Catholics, and Jewish recruits. My father brought in the first African American Navy chaplains, James R. Brown (African Methodist Episcopal) and Thomas David Parham (Presbyterian), to help with these ministries. Many recruits came from religious backgrounds, but for some this was their first exposure to religion of any kind. At their request, many were baptized or confirmed, carefully observing their religious preferences. My father also oversaw the famous Great Lakes Bluejacket Choir, under the musical direction of Chaplain H.F. Hanson. This choir consisted of 1,000 male voices singing together on any given Sunday, with a constant rotation of recruits cycling in and out of the Training Station. Divided into “choir companies” (120-130 recruits each) during the week, these recruits trained together and were often heard singing in four-part harmony as they marched along.

As a sea frontier chaplain for the Navy and Marines, Chaplain Johnny went to Okinawa and then the Philippines (Aug 1945-Aug 1946). Although the Pacific war ended in September 1945, marines at these outposts were still clearing out pockets of enemy resistance and rebuilding, and the situations were dangerous. At Okinawa my father’s private tent sat on the muddy outskirts of camp, and he carried no gun. His helmet and utility knife from that time are with me now. After a time as District Chaplain at Seattle, WA (Aug 1946-Jan 1949), he served with the Marines again at Pearl Harbor, HI (Feb 1949-July 1950), where he helped dedicate an early U.S.S. Arizona memorial and the Punch Bowl National Cemetery for American soldiers, sailors, and marines who died in the line of duty.

My father’s last post was District Chaplain of the Fifth Naval District, the largest in the Navy, headquartered at Norfolk (from Aug 1950). After 36 years, he retired from the Navy in June 1954.

For the next 12 years as a civilian pastor, Johnny turned his energies to ministry at the Bayside Presbyterian Church in Virginia Beach. Many members were Navy families, both active duty and retired, and the church thrived. When he retired from Bayside in 1967, the congregation gave him a garbage can, because, as the members said, “he always did whatever was needed, like taking out the garbage.” The church later made him Pastor Emeritus. He continued to serve as an interim or pulpit supply for thirty-nine more congregations in the area.

For as long as I can remember, my father worked on an old Remington portable typewriter, his constant companion at least as far back as Okinawa. He typed all his sermons, wrote all his letters, conducted all his business on that typewriter, and he refused to replace it. On the Saturday before he died at the age of 99+, a family discussion arose over a well-used computer that was on its way out. He said in a soft voice, “What are you going to do with the old computer? Maybe I could learn to use it.” I still have his typewriter.

In 1986 Pastor Johnny was asked to give a sermon for a Holy Week series, “If I Had Only One Sermon To Preach.” His topic was, “What shall we give in return for so much?” based on Matthew 16:26. His answer to the question was pure gratitude for the beauty and richness of human life—created and saved by God’s hand—and for “the pleasant surprise” of serving God through thick and thin. By this time, my father was unable to speak in public because of an operation to his jaw, so one of his sons delivered the sermon in his place. Still, Chaplain Johnny described the moment in a letter typed on his trusty Remington portable: “At the end of the sermon the entire congregation arose spontaneously and applauded vigorously.” Both the message and its reception capture the life, spirit, and ministry of Chaplain John Edward Johnson.

--Merwyn S. Johnson, ordained a Presbyterian minister in 1964, taught historical and systematic theology for 34 years at different seminaries, including Austin and Erskine. Now living in Charlotte, NC, he teaches off and on at Union Seminary, ministers at the non-profit In Christ Supporting Ministries (ICSM), and rears grandchildren. His most recent book is Bedrock for a Church on the Move (ICSM, 2019). Merwyn’s sister Carolyn and brother Tom helped with this essay on Chaplain Johnny.

Further Reading & Resources

Religion of Soldier and Sailor, ed Paul D. Moody. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1945. See "The Faith and Practice of the Raw Recruit," by John E. Johnson, pages 42-67.

Preachers Present Arms, Ray H. Abrams. New York City: Round Table Press, 1969. See Chapter 16: "The Churches and the Clergy in World War II." At PHS.

History of the Chaplain Corps United States Navy, 1778-1991, 12 volumes, compiled by Clifford M. Drury. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1948-2002. Some volumes at PHS.

Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. Chaplain’s Biographical Information Forms (3 vols.), Folio HAIC365. At PHS.

A Brief Chronology of the Chaplain Corps of the United States Navy, William F.R. Gilroy and Timothy J. Demy. At PHS.

Presbyterian Council for Chaplains and Military Personnel records, 14 0705. This is an unprocessed collection at PHS. Access to unprocessed collections and to records created within the last 50 years is restricted.

Presbyterian Council for Chaplains and Military Personnel website

John. E. Johnson personal papers. Presbyterian Heritage Center, Montreat, NC.