Miss Phillips at Odanah Mission

--by Linda Louise Bryan

I recently visited the Presbyterian Historical Society’s archives in search of Miss Harriet N. Phillips, whom I already knew from other contexts was a single white woman with a great desire to serve God and humankind. At 19th century missions, a woman was definitely in a man’s world, and yet females such as Phillips did a great deal of the mission work. I admire these unsung ladies, one of whose virtue and sacrifice I sing for you today.

PHS has records of Presbyterian outreach to American Indians that date back into the 18th century, but in this case I was looking for the 1870s. The records were originally organized when a curator’s approach was simpler: just number and bind all the mission-related letters and other papers in books and make a key as to what dates were covered in which bound volumes. Remnants of this once-logical—but preservation-challenged—system taunted later archivists who long ago unbound the letters and reports and put them into archival boxes. I definitely needed some guidance from the PHS archivists until the current system began to make sense to me. Once I figured out how to work between the old and new methods, things got speedier.

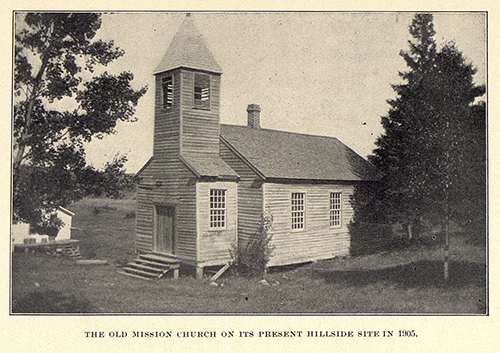

I already knew a bit about Miss Phillips’ service with the Ojibwe at the Odanah Mission in the 1870s, near today’s Ashland, Wisconsin. I had found yearly mention of her name in the Presbyterian Missions annual report rosters, but these gave little clue as to the real experience of Miss Phillips and her colleagues on the ground in Ojibwe country. Once I was able to physically handle letters and reports not only by Miss Phillips but also by her colleagues I discovered narratives: day-to-day and seasonal procedures; transportation arrangements; financial and school data; and anecdotes about the Protestant Ojibwe of northeastern Wisconsin, the Indian Agents, some mission donors, and a few early settlers at Bayfield and Ashland. Along the way, I handled pieces filed alongside the Ojibwe material: Pueblo, Nez Perce, Cherokee, and many more tribes. When I left at the end of my last day I had only read from 1872 to early 1875. For this reason alone I have vowed to return to PHS.

So what did I find during my visit? That Miss Phillips was a hard-working person and a real friend of the Indian. This was not news. But what I learned from her letters to her New York boss Rev. J.C. Lowrie, D.D. was surprising.

First of all, to overcome being female in a decidedly male world, Phillips used some smart rhetorical strategies in order to be heard. She was self-deprecating. She began sentences with coy phrasings like “I know you will find this letter a bother, but...” She praised men when they deserved praise and made sure that her criticisms of male colleagues were not personal but performance-based, such as: “He is so busy that he has no time to visit the sick with me” to illustrate why more staff were needed. She inquired about Lowrie’s health and often noted how busy and exhausted he must be, even when she really should have been writing in all-caps: “Do you realize we haven’t heard from you for months? Give us an honest update, fella!”

One particularly clever strategy was to admit that she was not an administrator (actually, no females were allowed to be one). And yet Phillips apparently assumed administrative control, with an apology, when expediency trumped gender protocols, such as when workers had to be hired to tie and store hay before it went bad, or when an important letter from the Indian Agency arrived while the new Mission Superintendent Rev. Isaac Baird was not on site. When Phillips first arrived, an incompetent superintendent was still in place, either suffering a breakdown or faking one. She took charge while the man dodged decision making and she tidied up after him when he left, organizing a mess of paperwork and finding ways to pay the most urgent bills, choosing which creditors would remain unpaid until funds were available. Rev. Baird gratefully listed her on one quarterly report as “Ass’t Superintendent,” acknowledging her capable work during a time of his absence.

Miss Phillips had strengths that others in the mission lacked. From my research elsewhere, I knew she was a trained nurse, having served in Union hospitals on the Mississippi during the Civil War and with Freedmen in the South after the war. She knew smallpox, secondary smallpox or “varioloid,” and how to prevent the disease from spreading. At Odanah she again faced off with smallpox, timing and phrasing her correspondence announcing an epidemic death rate so that the news would not alarm Lowrie.

Phillips was not only good at nursing but also at social work, matching up the needy with their needs, especially clothing for the Indians that she solicited through a personal network of needlewomen and money donors back in Philadelphia and elsewhere, women like herself who recognized the value of a sturdy garment. She addressed an urgent need of the teachers by locating a donor who would finance the re-publication of out-of-print Ojibwe language materials for the mission’s schools. She magically masterminded a donation of foodstuffs, coverlets, and small children’s toys. She analyzed the output of the mission farm and told Lowrie that farming, although very successful, was devouring more time than it should; the farm’s output should be cut back in favor of the men doing work more appropriate for religious outreach.

With sensitivity, Phillips reported the fatigue of workers and begged for work breaks for the staff, then remained on the job while others went on furlough. With a student-teacher ratio of roughly 30 to 40 beginning learners per teacher (at first working through an interpreter), and despite or because of many students’ erratic attendance during sugaring, hunting or fishing seasons, the teaching staff definitely needed a break.

Phillips found local workers and equipment to address problems with laundry and solicited two sewing machines, one for heavy duty, so that durable clothing could be constructed for the twenty-five voluntary boarding school “scholars.” She was deferential and thoughtful of aging Henry Blatchford, a full-blood lay preacher and interpreter who was essential for the operation of the mission, urging fruitlessly that he be ordained. Unlike materials I have examined from other mission operations, Odanah in the 1870s appears to have had a somewhat democratic decision-making process: Superintendent Baird shared Lowrie’s letters with the female staff and together they discussed the implications of Lowrie’s directives.

When Baird learned that after four years of service Phillips was contemplating a permanent departure, he must have felt that he was losing his right hand. This was as far as I was able to proceed in the PHS archives during my visit, but it left me hankering for more. What was Administrator Lowrie’s response? I look forward to finding it.

--

Linda Louise Bryan is a resident of Maplewood, MN. Her research at PHS has focused on Harriet Phillips, the Odanah Mission, and Henry Blatchford.

To see the recently revised finding aid for the American Indian Correspondence Record Group 224, click here.